This week, I wanted to put together some thoughts on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) gathered from across the web. Actually, this is the only story I've wanted to write about, but I haven't sat down for my #TWIST note in about a month.

In fact, I'm not sure there has been any story worth looking into except hurricane impacts on communities and infrastructure when we're talking about infrastructure and infrastructure resilience. Hurricanes Harvey and Irma are crucial because, if nothing else, they demonstrate to us that community resilience has everything to do with the communities' and local government leaders' capacity to respond in the moment and adapt to future possibilities. While it is important to build infrastructure that can withstand a variety of challenges, there are two things we must consider when planning for resilience. First, infrastructure is almost impossible to adapt after it is built. One can harden existing infrastructure, but infrastructure is almost, by definition, completely un-adaptive. Second, the radically de-centralized way in which infrastructure is owned and built--especially in the United States (and I include buildings in infrastructure, which many researchers do not)--makes it nearly impossible to forecast the types of loads that individual systems will be called on to respond to.

Well, I don't want to go too far into that direction. However, I did want to share some stories about the NFIP because we are going to need to call on this program more frequently and deeply in the future. What are the major issues? Is the program vulnerable? Are folks who rely on the program vulnerable? What kind of losses will it be called on to insure in the future? Hopefully, a few of the articles/resources below can shed some light on the state of the NFIP as we enter into new climate realities.

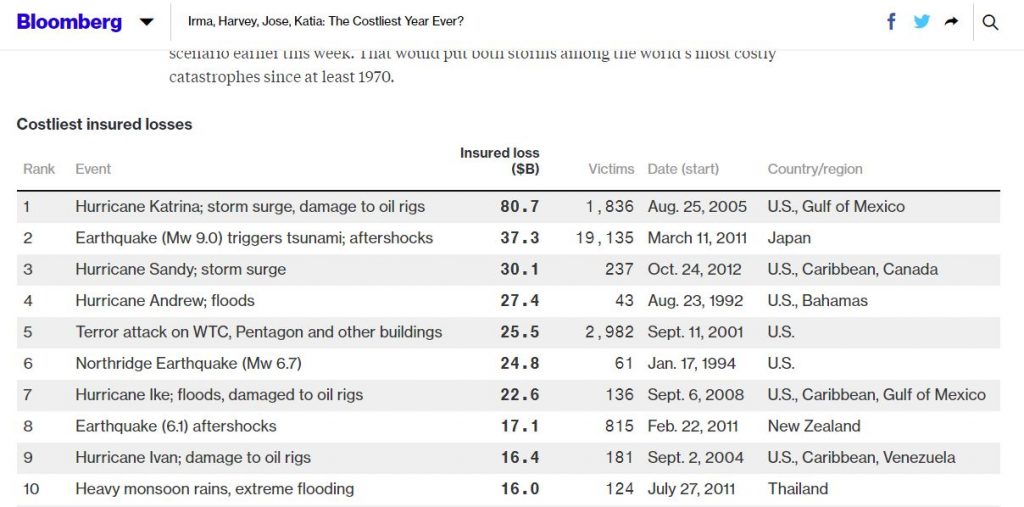

- Irma, Harvey, Jose, Katia: The Costliest Year Ever? Bloomberg asks whether Harvey et al will be among the costliest disasters ever. A snapshot from their article demonstrates that, globally, American hurricanes are responsible for five of the top 10 most costly events--in terms of insured losses. Where will this year's hurricane season rank?

The 10 most costly global disasters in terms of insured losses (in Billions). Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2017-costliest-insured-losses/ - Hurricane Sandy Victims: Here’s What ‘Aid’ Irma and Harvey Homeowners Should Expect. While it is critical to re-authorize NFIP and help to ensure that families receive the aid they need, it is unclear whether NFIP in its current form can deliver that assistance. Writing in Fortune Magazine describing the efforts of a group called Stop FEMA Now to promote awareness about some of the major shortcomings (as they see it) of NFIP, Kirsten Korosec writes:

Stop FEMA Now is a non-profit organization that launched after flood insurance premiums spiked as a result of the Biggert-Waters Act of 2012, inaccurate or incomplete FEMA flood maps, and what it describes as questionable insurance risk and premium calculations by actuaries, according to the group.

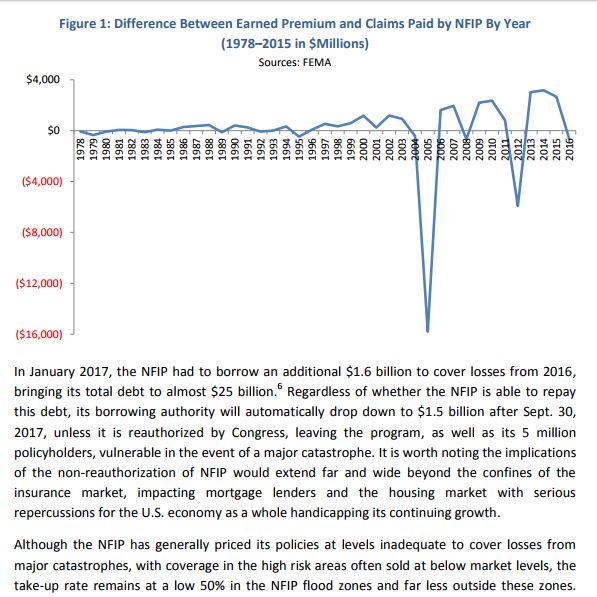

- The NAIC has published a very interesting report that shows that, in the average year, NFIP is self-supporting. While in most years it pays out fewer claims that it receives in premiums, catastrophes are well beyond their capability to pay and NFIP must rely on borrowing. Consider Figure 1 from their report:

Difference between NFIP premiums and claims per year. Source: <http://www.naic.org/documents/cipr_study_1704_flood_risk.pdf> Do you see what they say in those two paragraphs after the figure?! First, note that NFIP must have its borrowing authority reauthorized by Congress before Sep. 30 (it has been extended to Dec. 8), and that it is already $25 billion in debt. Second, note that the NFIP has not priced its policies at "market rates," making NFIP unable to cover losses from major catastrophes. Even with these artificially low rates, vulnerable parties do not purchase the insurance!

- Finally, J. Robert Hunter writes in the Hill about the fact that NFIP originally contained long-range planning in the legislation. Nonetheless, communities are not enforcing the land-use provisions contained in the law:

When I ran the NFIP in the 1970s, I saw a far-sighted idea that Congress put into action. Congress brilliantly embedded long-range planning into the program: in exchange for subsidies for flood insurance on then existing homes and businesses, communities would enact and enforce land use measures to steer construction away from high-risk areas and elevate all structures above the 100-year flood level. Only pre-1970s structures would be subsidized.

Clearly, from the snippets I've placed here for you, NFIP is in trouble. This is the story. How much longer can we afford to ignore the state of NFIP as a major tool for supporting community resilience?